It’s time for a Christmas post. This may be out of period for us, but we can do a little digging into an obscure modern legend.

Europe became Christian around 400 AD, and Christmas itself originates in Rome in 336 AD. But the first documented example of a Christmas tree at Christmas is in a register in the town hall of Séléstat in deeply Catholic Alsace, dated 1521.

However there is a low-visibility rumour going around that prior to this, in the 1400s, there was a Christmas tree used in Livonia, in the city of Reval. Today, after the 1945 deportation of the Baltic Germans, Reval is called Talinn, and Livonia is called Estonia.

This claim may be found presently in the Wikipedia article:

Customs of erecting decorated trees in wintertime can be traced to Christmas celebrations in Renaissance-era guilds in Northern Germany and Livonia. The first evidence of decorated trees associated with Christmas Day are trees in guildhalls decorated with sweets to be enjoyed by the apprentices and children. In Livonia (present-day Estonia and Latvia), in 1441, 1442, 1510, and 1514, the Brotherhood of Blackheads erected a tree for the holidays in their guild houses in Reval (now Tallinn) and Riga. On the last night of the celebrations leading up to the holidays, the tree was taken to the Town Hall Square, where the members of the brotherhood danced around it.

This is backed by a “reference” which, as is too common, does not say all this: “Amelung, Friedrich (1885). Geschichte der Revaler Schwarzenhäupter: von ihrem Ursprung an bis auf die Gegenwart: nach den urkundenmäßigen Quellen des Revaler Schwarzenhäupter-Archivs 1, Die erste Blütezeit von 1399–1557“. This may be found here, in a PDF with nice OCR.

It doesn’t take much searching to find an article at NPR where someone more informed than any of us are likely to be pours cold water on the claim. But I thought it might be fun to look at the sources.

Amelung in fact directs the reader to something called the “Livonian Chronicle” by a certain Balthasar Rüssow, who published a Chronica der Provinz Lyfflandt in low German in1578. A revised edition appeared in 1584, and may be found here.

Fortunately for the rest of us, it was translated into standard German and printed in 1845, and is available here and here, under the revised title of

Livländische Chronik: Aus dem Plattdeutschen übertragen und mit kurzen Anmerkungen versehen durch Eduard Pabst.

The work does seem to be known most generally as Balthasar Rüssow’s “Livländlische chronik” or “Livonian Chronicle”. No English translation exists.

P. 68 has two chapters of dated events, to 1547. P. 69 has chapter 48 dated to 1549-51. So there is some chronological order to this. But we are interested in the next chapter.

Chapter 49 bears the heading, “Die alte gute Zeit in Livland”, “The good old days in Livonia”. It is this that contains the words “Tannenbaum” and “Weihnachtsbaum”, in the following short section on p.82-3. The context is a discussion of celebrations at various times of the year.

I will give the German, then a slightly revised version of Google Translate, as most of this doesn’t matter much. I don’t guarantee the translation: I haven’t much time this evening, and German is not my language. But we can get an idea. The author was a Lutheran clergyman, as is perhaps clear from some of what he says.

… Und wenn sie den halben Lag über den Vogel geschossen und ihn herunter gebracht hatten, da wurde stracks dem neuen Könige mit großem Frohlocken von Jedermann Glück und Heil gewünscht. Da war dann keine geringe Freude bei des Königs Freunden und auch bei Denen, die auf ihn gewettet und gewonnen hatten. Nicht lange darnach wurde derselbige neue König mit Posaunen und mit der vorigen Procession aller Gildenbrüder zwischen den zweien Aeltesten der Gemeine durch die Stadt nach der Gildenstube begleitet. Da stund es vor allen Thüren voll Volks von Männern, Frauen, Jungfern, Kindern und allerlei Gesinde, welche den neuen König mit großer Verwunderung und Freude anschauten. Da mußte der König einen silbernen Vogel auf einer Stange in seiner Hand tragen, und sein stählerner Bogen samt dem Bolzen, da er den Vogel mit herunter geschossen hatte, wurde hoch vor ihm her getragen. Und wenn sie in die Gildenstube kamen, da Alles herrlich und wohl zugerichtet war, dann find da ihre Frauen und Töchter zu demselbigen Bankett auch vor-Handen gewesen. Da hat man dem Könige von den schmuckesten Jungfern eine Königinn erwählt, die bei ihm allein stets sitzen und tanzen mußte, unangesehen daß er eine Frau hatte. Und solch ein Fest der Vogelstange hat drei der nächsten Sonntage nach Ostern gewährt, weshalb die Prediger diese drei Sonntage Nachmittags gemeinlich gefeiert haben, dieweil sich Jedermann lieber bei der Vogelstange als in der Kirche finden ließ.

Auf Pfingsten sind die Bürger und Gesellen in den Mai geritten und haben dar einen Maigrasen, der am Beßten ein herrlich Bankett auszurichten 1) vermöchte, unter sich erwählt und mit großem Pompe eingeführt.2) Solche Maigrafschaften sind darnach von Jedermann und auch von dem gemeinen Pöbel den ganzen Sommer durch alle Sonntage gehalten worden, nicht ohne vielfältige Leichtfertigkeit. So waren auch noch sonderliche Vogelstangen etlicherwegen an lustigen Oertern aufgerichtet, dar die jungen Ordensherren, Bürger und Gesellen alle Sonntage den ganzen Sommer durch den Vogel um ein Kleinod geschossen haben, da denn viel Volks, jung und alt, bei Haufen sich hin verfügt, solche Kurzweil anzuschauen, und den Sonntag also zugebracht hat.

Dieweil solch Vogelschießen bei den jungen Ordensherren, Bürgern und Kaufgesellen in hohem Preise war, da begannen die vom Adel etlicherwegen solcher Kurzweil sich auch zu befleißigen und Vogelstangen bei ihren Pfarrkirchen kurz vor der Livländischen Veränderung aufzurichten, dahin denn Viele gegen das Pfingstsest über zehn Meilen Wegs um der Vogelstange willen gekommen sind, und sich mehr um das Vogelschießen als um Gottes Wort bekümmert haben. Mittlerweile, wenn sie über dem Vogel schössen, wurde ein herrlich Bankett in des Pastors Hause zugerichtet, wo sie sich über ihr Vogelschießen lustig und guter Dinge machten.

So haben auch die Bürger bei Wintertagen in Weihnachten und Fastnacht auf ihren Gildenstuben, und die Gesellen 3) in ihren Companieen eine nicht geringe Wollust 4) geübt. Und wenn der Kaufgesellen Trunk 5) ein Ende hatte, haben sie einen großen hohen Tannenbaum, mit vielen Rosen behängen, in den Fasten auf dem Markte aufgerichtet und sich gegen den Abend gar spät mit einem Haufen Frauen und Jungfrauen dahin verfügt, erstlich gesungen und geschlungen und darnach den Baum angezündet, welcher im Düstern gewaltig geflammt hat. Da haben die Gesellen sich unter einander bei der Hand gefaßt und bei Paaren um den Baum und um das Feuer her gehüpft und getanzt, dar auch die Feuerwerker Raketen zur Pralerei schießen mußten. Und wiewol Solches von den Predigern gestraft, ist doch solche Strafe gar nichts geachtet worden. Zudem ist dar auch mit dem Ringfahren 6) mit Frauen und Jungfern weder Maß noch Ende gewesen, beides Tag und Nacht und oftmals den Predigern, die Solches gestraft, zu Trotze und zu Leide.

Diese vorerwähnte große Wollust der Livländer ist dem Muskowiter sehr zuträglich gewesen; denn in solchem Wesen hat er auf seine rechte Zeit, Anschläge und Vortheil gedacht und sich auf Geschütz, Kraut und Loth 7) und auf allerlei Kriegsmunition gewaltig und überflüssig geschickt und den einen Büchsenmeister nach dem andern aus den Deutschen und Welschen Landen erlangt. Und wiewol die Livländer Solches alle- wol wußten, so waren sie doch in großer Wollust und Sicherheit so ganz ersoffen, daß sie es nicht achten konnten, sondern ihm noch Kupfer, Blei und allerlei Waare, so zu seinem Vornehmen wider Livland gedient, ganz überflüssig zugeführt, heimlich und öffentlich, wie Solches aller Welt bewußt ist.

Which comes out as:

And when they had shot half the lag at the bird and brought it down, everyone wished luck and salvation to the new king with great joy. There was then no small joy among the king’s friends and also among those who had bet and won on him. Not long afterwards the same new king was accompanied with trumpets and with the previous procession of all guild brothers between the two elders of the community through the city to the guild room. There was a crowd of men, women, maidens, children, and all kinds of servants at every door, who looked at the new king with great astonishment and joy. Then the king had to carry a silver bird on a pole in his hand, and his steel bow with the bolt, which he had shot down the bird with, was carried high in front of him. And when they came to the guild room, since everything was splendidly and well prepared, then their wives and daughters were also there for the same banquet. A queen was chosen for the king from the finest maidens, who always had to sit and dance with him alone, regardless of the fact that he had a wife. And such a feast of the birdpole happened for three of the next Sundays after Easter, which is why the preachers celebrated these three Sundays in the afternoons, as everyone preferred to be found at the birdpole than in church.

At Pentecost, the citizens and journeymen rode into May and chose a “May meadow”, where they could be able best to hold a glorious banquet among themselves and introduced it with great pomp. Such May festivities were kept by everyone, and also by the common people, all summer, every Sundays, not without a variety of levity. So there were also special bird poles set up at places of amusement, so that the young knights of the order, citizens and journeymen shot at the bird for a reward every Sunday throughout the summer, because a lot of people, young and old, wanted to have a go at this for a short time, and so they spent the Sunday.

Because such bird shooting was so prized among the young monks, burghers and merchants, the nobility began to work hard because of such entertainment and to set up bird poles in their parish churches shortly before the Livonian change, there because many at Pentecost over ten miles away came for the sake of the birdpole, caring more about bird-shooting than about God’s word. Meanwhile, when they shot at the bird, a wonderful banquet was set up in the pastor’s house, where they celebrated their bird shooting and in good spirits.

The citizens, too, have exercised considerable fun in their guild rooms on winter days in Christmas and Shrovetide, and the journeymen in their companies. And when the journeyman drinks had finished, they would set up a tall, tall Christmas tree, hung with many roses, in the market during the fasting and, late in the evening, arranged to go there with a bunch of wives and girls, first of all singing and dancing around it and afterwards set fire to the tree, which in the gloom flamed mightily. Then the journeymen took each other by the hand and jumped and danced around the tree and around the fire with couples, and let off firework rockets to celebrate. And however much the preachers preached against such things, such preaching was not at all respected. In addition, there was neither measure nor an end to the ring dancing with wives and girls, both day and night and often to defy and ignore the preachers who criticised such things.

This great celebration of the Livonians, mentioned above, was very beneficial to the Muscovite; for in such a manner he thought this was the right time, to plan attacks and advantages and he made great use of guns, kraut and loth, and all kinds of ammunition, and obtained one gunsmith after the other from the German and French lands. And although the Livonians knew this, they were so completely drowned in their great amusements and security that they could not pay attention to it; and he brought in the copper, lead and all sorts of materials, used in his campaign against Livonia, quite superfluously, secretly and publicly, as all the world knows.

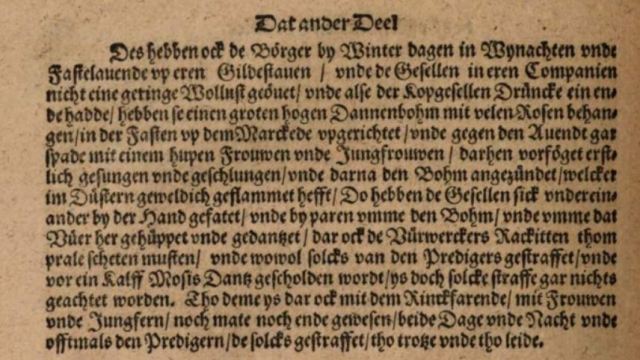

Here’s the same material from the 1584 edition in low German:

So this “Christmas tree” (Tannenbaum – Dannenbaum in low German) as Russow calls it was set up in the winter days of Christmas and also at the start of Lent (Fastnacht), decorated with roses, and then burned as part of the festivities. He is writing much later, at a time when Christmas trees are widespread. It would be interesting to know what it was actually called at the time.

But burning Christmas trees and dancing around them isn’t really what we do, or not intentionally so. So, on the face of it, this is a related idea, from the same period, and the same culture; a cousin of the Christmas tree, rather than its origin.

Hello Roger,

Thank you as always for your good work. Just a quick note on the origins of Christmas, there is some evidence that the Dec. 25 date was chosen as the birth of Jesus a century before 336 AD, which I detail in my article found here

https://www.academia.edu/18110500/Calculating_December_25_as_the_Birth_of_Jesus_in_Hippolytus_Canon_and_Chronicon_Vigiliae_Christianae_69_5_2015_542_63

Briefly, it seems likely (though not conclusive) that Dec. 25 was chosen by Hippolytus and perhaps also by Julius Africanus in the 220s AD. Clement of Alexandria shows similar chronological persuasions, but relied on the Egyptian calendar (not the Roman) and so witnesses to a slightly different date.

Merry Christmas!

Tom

Hi Tom, Thank you for this! I was aware of your work on this, but it’s hard to know whether Hippolytus’ statement reflects an official view, or a personal calculation. So I didn’t base anything on it.

Yes, but do remember that the Chronography of 354 (where the 336 AD date for Christmas is found) is based on Hippolytus’ Chronicon, which seems to have also dated Jesus birth to Dec. 25. So it is plausible that the Chronography of 354 took the date from Hippolytus. But, whatever the case, have a wonderful Christmas!

I wasn’t aware of any connection between the two texts…?

Yes, Hippolytus’ Chronicon is largely taken up directly into the Liber Generationis which is in part 15 of the Chronography of 354. In Hippolytus’ Chronicon §686-687 (corresponding to Liber Gen. I §301 and the Armenian version §269) it states that Jesus was born 5,502 years and 9 months after the creation of the world. Hippolytus elsewhere implies that the creation of the world occurred on March 25, so 9 months from that is December 25.

The Chronography of 354 also has unique info on Hippolytus in Part 12 and Part 13 (Mommsen, Chronica Minora vol. 1 p. 72, 74-75), hence it seems likely that the author of the document knew of his work.